By: Joceyln Knorr

May, 1943. Operation Torch, the Allied tank invasion of North Africa, has just come to a close. Now, they are staring down the barrel of a much larger invasion—the Nazis have occupied Europe entirely, and are threatening to make the jump to the UK, too. It’s only obvious where the Allied forces will land; the Allies hold the strategic port of Tunis, and it’s only logical to make the landing from there. As such, Mussolini and Hitler have predicted an invasion, reinforcing the island with 100,00 troops. If the Allies make the landing there, they will surely be rebuffed; the task is now to divert the troops, and make sure that they’re expecting the landing anywhere else.

Enter Ian Fleming, personal assistant to Rear Admiral John Godfrey and future author of the James Bond novels. In 1939, he penned a document called the “Trout Memo;” it outlined several scenarios and strategies that may be applied when in need of a way to deceive the Axis Powers. At the time, the Trout Memo was considered outlandish, and it was shelved. However, in 1942, this memo was picked up by one Lieutenant Charles Cholmondeley. He was inspired by a suggestion in the Trout Memo—using a planted corpse with fake documents to lure German U-Boats towards mines—and the Turner crash—an American officer had died in a plane crash in 1942 after the engine failed over neutral Spain; forensic analysis of the classified documents he was carrying had indicated that they were copied by the Nazis—to write up his own plan. The plan was thus; a fresh corpse of service age, preferably deceased via drowning, would be obtained. He would be dressed in a uniform, forged documents attached to his person, and be delivered via submarine to Spain, where the fake information would be passed on to the Nazis.

This plan was accepted after a few minor alterations, and Cholmondeley was put in contact with Lieutenant Commander Ewen Montagu, the Navy liaison to Military Deception. Together, they sourced a body, procured from a coroner that Montagu knew from his lawyer days. The provenance of this body is highly disputed. Historians generally agree that the man was Glyndwr Michael, an unhoused man who came to London from Cardiff for work and died after eating rat poison. However, there is a small minority contingent that believe the body used was one of the men from the HMS Dasher, an aircraft carrier that took a hit in March of 1943. Either way, the body was used without the knowledge, and certainly not the consent, of the family.

With the corpse secured, Cholmondeley and Montagu set to work creating his new identity. A common surname, a rank of high enough importance to be carrying classified information, and a department that could direct inquirers to Naval intelligence all coincided, creating Captain (Acting Major) William “Bill” Martin. Next, they had to equip him with documents of the sort one might realistically carry on one’s person, reinforcing the illusion that this man was real. A fiancee was invented for Martin, by the name of Pam; a photo was provided by Jean Leslie, a secretary at MI5. Personal correspondence was also included, along with pocket change, stamps, and a medallion of St. Christopher. This was unusual in officially-Anglican England, but the justification was that Spain was mostly Roman Catholic—if the administrators handing the body saw him as a member of their community, they might be more inclined to trust him, and therefore the information he was carrying.

The deception itself took the form of personal correspondence between Lieutenant General Sir Archibald Nye and General Sir Harold Alexander. Several drafts were done, but were found unsatisfactory—eventually, they got Nye himself to write the letter, indicating that the British Army were to land at Greece, and their cover target was Sicily.

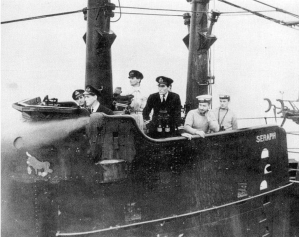

With all their ducks finally in a row, Cholmondeley and Montagu passed the corpse off to the crew of the HMS Seraph, a submarine used in covert operations. Acting Major Martin was launched on April 30th, surfacing in Huelva later that same day. Vice-consul of Spain Francis Haselden had been briefed beforehand, and knowing that the security of British diplomatic telegraphs had been breached, stressed the importance of the documents and how swiftly they had to be returned to British soil. Martin himself was autopsied and buried with honors, while his briefcase was passed along to Cadiz; there, it caught the attention of Karl-Erich Kühlenthal, one of the top agents in the German spy network. From Kühlenthal, the documents were passed onto Berlin, and eventually made it onto the desk of Hitler himself. Convinced that the documents were legitimate, German high command transferred their troops from Sicily to Greece in late May.

No official estimates of the impact of Operation Mincemeat have ever been undertaken, but casualties on both the Allied and Axis sides were few, owing to the small amount of troops that remained concentrated on the island. Most notably, the invasion led to the fall of Mussolini’s dictatorship and the return of leadership to King Victor Emmanuel III, who pulled out of the war afterwards. Captain Martin’s memorial in Spain has since been amended; it now indicates that the deceased’s name was Glyndwr Michael, serving under the name of William Martin. A short service, indeed, but one that saved countless lives.